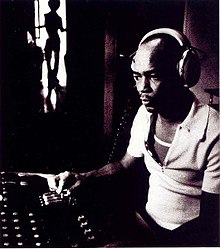

King Tubby

King Tubby | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Osbourne Ruddock |

| Born | 28 January 1941 |

| Origin | Kingston, Jamaica |

| Died | 6 February 1989 (aged 48) Kingston, Jamaica |

| Genres | |

| Occupations | |

| Years active | 1968–1989 |

| Labels | Firehouse, Kingston 11, Waterhouse, Taurus |

Osbourne Ruddock (28 January 1941 – 6 February 1989), better known as King Tubby, was a Jamaican sound engineer who influenced the development of dub music in the 1960s and 1970s.[1][2]

Tubby's studio work, in which as a mixing engineer he achieved creative fame previously only reserved for composers and musicians, was influential across many genres of popular music. He is often cited as the inventor of the concept of the remix that later became ubiquitous in dance and electronic music production. Singer Mikey Dread stated, "King Tubby truly understood sound in a scientific sense. He knew how the circuits worked and what the electrons did. That's why he could do what he did".[3]

Career

[edit]In the late 1950s, Jamaican sound systems were becoming popular in Kingston and were developing into enterprising businesses. A radio repairman, Tubby found frequent work for the sound systems, as the tropical weather of the Caribbean island (often combined with sabotage by rival sound system owners) led to malfunctions and equipment failure.[4] Tubby owned an electrical repair shop on Drumalie Avenue, Kingston, that fixed televisions and radios.[2] He built large amplifiers for the local sound systems.[2] In 1961–62 he built his own radio transmitter and briefly ran a pirate radio station playing ska and rhythm and blues which he soon shut down when he heard that the police were looking for the pirate broadcasters.[5] Tubby eventually formed his own sound system, Tubby's Hometown Hi-Fi, in 1958.[4][6] It was popular due to the high quality of his equipment, exclusive releases and Tubby's own echo and reverb sound effects, at that point a novelty which had not been created outside of a studio setting.[2][7] The sound also launched the career of U-Roy, its featured toaster.[8]

Remixes

[edit]Tubby began working as a disc cutter for producer Duke Reid in 1968.[4] Reid, one of the major figures in early Jamaican music alongside rival Clement "Coxsone" Dodd, ran Treasure Isle studios, one of Jamaica's first independent production houses, and was a key producer of ska, rocksteady and eventually reggae recordings. Before the advent of dub, most Jamaican 45s featured an instrumental version of the main song on the flipside, which was called the "version". When Tubby was asked to produce versions of songs for sound system MCs or toasters, he initially worked to remove the vocal tracks with the faders on Reid's mixing desk, but soon discovered that the various instrumental tracks could be accentuated, reworked and emphasised through the settings on the mixer and early effects units.[2] In time, Tubby began to create wholly new pieces of music by shifting the emphasis in the instrumentals, adding sounds and removing others and adding various special effects, like extreme delays, echoes, reverb and phase effects.[3] Partly due to the popularity of these early remixes, in 1971, Tubby's soundsystem consolidated its position as one of the most popular in Kingston and Tubby decided to open a studio of his own in Waterhouse in 1971, initially using a 4-track mixer purchased from Byron Lee's Dynamic studio.[4][6]

Dub music production

[edit]King Tubby's production work in the 1970s made him one of the best-known celebrities in Jamaica, and generated interest in his production techniques from producers, sound engineers and musicians across the world. Tubby built on his knowledge of electronics to repair, adapt and design his own studio equipment, which made use of a combination of old devices and new technologies to produce a studio capable of the precise, atmospheric sounds which would become Tubby's trademark. With a variety of effects units connected to his mixer, Tubby "played" the mixing desk like an instrument, bringing instruments and vocals in and out of the mix to create an entirely new genre known as dub music.[3] By the end of 1971 he was already providing dub mixes for producers such as Glen Brown and Lee "Scratch" Perry.[4]

Using existing multitrack master tapes—his small studio in fact had no capacity to record session musicians—Tubby re-taped, or "dubbed", the original after passing it through his 12-channel, custom-built MCI mixing desk, twisting the songs into unexpected configurations which highlighted the heavy rhythms of their bass and drum parts with minute snatches of vocals, horns, piano and organ.[2] These techniques mirrored the actions of the sound system selectors (reggae disc jockeys), who had long used EQ equipment to emphasise certain aspects of particular records, but Tubby used his custom-built studio to take this technique into new areas, often transforming a hit song to the point where it was almost unrecognisable from the original version. One unique aspect of his remixes or dubs was the result of creative manipulating of the built-in high-pass filter on the MCI mixer he had bought from Dynamic Studios. The filter was a parametric EQ which was controllable by a large knob—a.k.a. the "big knob"—which allowed Tubby to introduce a dramatic narrowing sweep of any signal, such as the horns, until the sound disappeared into a thin squeal.[citation needed]

Tubby engineered/remixed songs for Jamaica's top producers such as Lee Perry, Bunny Lee, Augustus Pablo and Vivian Jackson, that featured artists such as Johnny Clarke, Cornell Campbell, Linval Thompson, Horace Andy, Big Joe, Delroy Wilson and Jah Stitch.[4][6] In 1973, he added a second 4-track mixer, and built a vocal booth at his studio so he could record vocal tracks onto the instrumental tapes brought to him by various producers.[4] This process is known as "voicing" in Jamaican recording parlance. It is unlikely that a complete discography of Tubby's production work could be created based on the number of labels, artists and producers with whom he worked, and also subsequent repressings of these releases sometimes contained contradictory information. His name is credited on hundreds of B-side labels, with the possibility that many others were by his hand yet uncredited, due to similarities with his known work. Several albums of Tubby's dub mixes were released, among the earliest the Perry-produced Blackboard Jungle and Bunny Lee's Dub from the Roots (both 1974).[4]

His most famous dub and one of the most popular dubs of all time was "King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown" from 1974.[9] The original session was for a Jacob Miller song called "Baby I Love You So", which featured Bob Marley's drummer Carlton Barrett playing a traditional one drop rhythm. When Tubby completed the dub, which also featured Augustus Pablo on melodica, Barrett's drums regenerated several times and created a totally new rhythm which was later tagged "rockers". This seminal track later also appeared on Pablo's 1976 album King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown.

By the later part of the 1970s, King Tubby had mostly retired from music, still occasionally mixing dubs and tutoring a new generation of artists, including King Jammy and perhaps his greatest protege, Hopeton Brown a.k.a. Scientist.[4] In the 1980s, he built a new, larger studio in the Waterhouse neighbourhood of Kingston with increased capabilities, and focused on the management of his labels Firehouse, Waterhouse, Kingston 11, and Taurus, which released his productions of Anthony Red Rose, Sugar Minott, Conroy Smith, King Everald and other popular musicians.[4][6]

Death

[edit]King Tubby was shot dead on 6 February 1989, outside his home in Duhaney Park, Kingston, upon returning from a session at his Waterhouse studio. His death was believed to be the outcome of a robbery.[4][10]

Discography

[edit]With Augustus Pablo

[edit]- Ital Dub (1974, Starapple/Trojan Records)

- King Tubbys Meets Rockers Uptown (1976, Yard Music/Clocktower Records)

- Original Rockers (1979, Rockers International/Greensleeves Records/Shanachie Records)

- Rockers Meets King Tubbys in a Firehouse (1980, Yard Music/Shanachie)

With The Aggrovators

[edit]- Shalom Dub (1975, Klik)

- Dubbing in the Backyard (1982, Black Music)

With Prince Jammy

[edit]- His Majestys Dub (1983, Sky Juice)

- First, Second and Third Generation of Dub (1981, KG Imperial)

With Lee "Scratch" Perry

[edit]- Upsetters 14 Dub Blackboard Jungle (a.k.a. Blackboard Jungle Dub) (1973, Upsetter Records)

- King Tubby Meets the Upsetter at the Grass Roots of Dub (1974, Fay Music/Total Sounds)

- Dub from the Roots (Total Sounds, 1974, Total Sounds)

- Creation of Dub (1975, Total Sounds)

- The Roots of Dub (a.k.a. Presents the Roots of Dub) (1975, Grounation/Total Sounds)

- King Tubby Meets Vivian Jackson (a.k.a. Chant Down Babylon and Walls Of Jerusalem) (1976, Prophet)

- King Tubby's Prophecy of Dub (a.k.a. Prophecy of Dub) (1976, Prophets)

Other collaborations

[edit]- Niney the Observer – Dubbing with the Observer (1975, Observer/Total Sounds)

- Harry Mudie – In Dub Conference Volumes One, Two & Three (1975, 1977 & 1978 Moodisc Records)

- Larry Marshall – Marshall (1975, Marshall/Java Record)

- Roots Radics – Dangerous Dub (1981, Copasetic)

- Waterhouse Posse – King Tubby the Dubmaster with the Waterhouse Posse (1983, Vista Sounds)

- Sly & Robbie – Sly and Robbie Meet King Tubby (1984, Culture Press)

Compilations

[edit]- King Tubby & The Aggrovators – Dub Jackpot (1990, Attack)

- King Tubby & Friends – Dub Gone Crazy - The Evolution of Dub at King Tubby's 1975-1979 (1994, Blood & Fire)

- King Tubby & The Aggrovators & Bunny Lee – Bionic Dub (1995, Lagoon)

- King Tubby & The Aggrovators & Bunny Lee – Straight to I Roy Head 1973–1977 (1995, Lagoon)

- King Tubby & Scientist – At Dub Station (1996, Burning Sounds)

- King Tubby & Scientist – In a World of Dub (1996, Burning Sounds)

- King Tubby & Glen Brown – Termination Dub (1973-79) (1996, Blood & Fire)

- King Tubby & Soul Syndicate – Freedom Sounds In Dub (1996, Blood & Fire)

- King Tubby & Friends - Crucial Dub (2000, Delta)

- King Tubby & The Aggrovators – Foundation of Dub (2001, Trojan)

- King Tubby – Dub Fever (2002, Music Digital)

- African Brothers Meet King Tubby – In Dub (2005, Nature Sounds)

- King Tubby - Hometown Hi-Fi (Dubplate Specials 1975-1979) (2013, Jamaican Recordings)

References

[edit]- ^ Stratton, Jeff (3 March 2005). "Dub from the Roots". Miami New Times. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Colin Larkin, ed. (1992). The Guinness Encyclopedia of Popular Music (First ed.). Guinness Publishing. pp. 1380/1. ISBN 0-85112-939-0.

- ^ a b c Du Noyer, Paul (2003). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Music (1st ed.). Fulham, London: Flame Tree Publishing. pp. 356–357. ISBN 1-904041-96-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Thompson, Dave (2002) Reggae & Caribbean Music, Backbeat Books, ISBN 0-87930-655-6, pp. 138–141

- ^ "King Jammy interview", BBC, 2005. Retrieved 30 April 2016

- ^ a b c d Bonitto, Brian (2012) "King Tubby, the sound creator Archived 30 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine", Jamaica Observer, 6 July 2012, retrieved 13 July 2012

- ^ Bradley, Lloyd (2002). Reggae: The Story of Jamaican Music. London, UK: BBC Worldwide. p. 32-33. ISBN 0563488077.

- ^ Masouri, John (2009). Wailing Blues: The Story of Bob Marley's Wailers. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0857120359. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ "1000 albums to hear before you die: Artists beginning with P". The Guardian. 21 November 2007.

- ^ "Icon – King Tubby reigns". Jamaica Gleaner News. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

External links

[edit]- Discography at Roots Archives

- Discography of 1970's recordings & dub sources at X Ray Music

- King Tubby discography at Discogs